In today’s wellness-driven culture, fasting has taken on renewed importance as a health and spiritual tool. Many people turn to fasting as a means to cleanse their bodies, shed unwanted pounds, or develop greater mental clarity. It can indeed offer these benefits, yet, like many practices, it should not be undertaken without the necessary mindfulness and sensitivity.

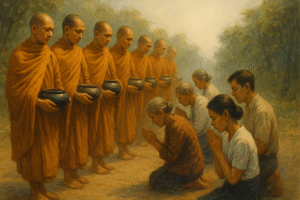

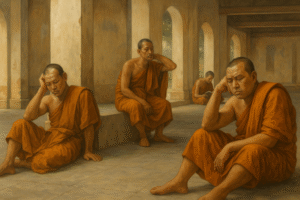

The spiritual teachings of Gautama Buddha provide a compelling example. As the progenitor of Buddhism, one of the world’s major religions, Buddha embarked on a transformative journey that initially involved extreme fasting. He subjected himself to years of starvation in his quest for enlightenment, only to find that the path of self-denial did not yield the profound understanding he sought. It was only when Buddha embraced the Middle Way – a path of moderation and balance between deprivation and indulgence – that he achieved the enlightenment he sought. This story offers valuable lessons for our approach to fasting today.

First and foremost, the practice of fasting is not about starvation or deprivation. It is about developing a more nuanced relationship with our bodies and the sustenance they require. Fasting can indeed help to cleanse the body, but it is not a cure-all solution. It is a tool for enhancing our health, not a substitute for a balanced diet and regular exercise. Furthermore, extreme fasting, as Buddha discovered, can be counterproductive. Our bodies need nourishment to function, and denying them essential nutrients can lead to a host of physical and mental health issues.

However, when used appropriately, fasting can bring awareness and sensitivity to our eating habits. It forces us to pay attention to our hunger cues, to understand when we are truly hungry and when we are simply responding to external stimuli. It encourages us to take note of what we eat and how it affects our bodies, bringing about a new level of mindfulness. In a sense, fasting is less about the act of not eating, and more about learning to eat with awareness and intention.

The spiritual aspect of fasting focuses on its potential to strengthen our minds. When we fast, we train our minds to resist the allure of instant gratification and develop patience. This heightened awareness can extend to our overall life, encouraging greater consciousness in our choices and actions.

Understanding the food-body relationship is also an integral part of fasting. Food nourishes not only our bodies but also our minds. By becoming more conscious of how food affects our mental state, we can make better food choices that promote both physical and mental well-being.

Fasting, in its essence, should be a journey of self-discovery and personal growth. The process of denying oneself food for certain periods is a test of self-discipline, mental strength, and patience. As we navigate this journey, it is crucial that we remain aware of our bodies’ signals, sensitive to our needs, and committed to the philosophy of balance that Buddha so wisely espoused.

Fasting should not be an act of punishing the body but rather, it should be about loving oneself enough to give the body what it truly needs: nourishment, rest, and balance. Fasting without awareness and sensitivity can lead to more harm than good, and, as Buddha’s journey illustrates, the path to enlightenment and wellbeing is found not in deprivation, but in balance and mindful living.

The critical element often overlooked in the discourse surrounding fasting is the necessity of mental awareness and sensitivity. Fasting without these vital components can morph into repression, a potentially harmful pattern that can have far-reaching consequences. When we deprive our bodies of food without an understanding or awareness of why we are doing it, we can inadvertently fuel an intensified yearning and desire for food. This reaction can spiral into a cycle of deprivation and overindulgence, leading us further away from the balance we seek.

During the initial stages of fasting, it is paramount to start gradually and consciously. One cannot simply leap into a rigorous fasting regimen without first preparing the mind for this significant shift. In this phase, we must become keenly aware of our feelings and thoughts in relation to our food intake. This awareness forms the bedrock of a successful fasting practice. It necessitates observing our reactions to reduced food consumption, understanding our genuine hunger cues, and becoming aware of the feelings of fullness.

For example, we may discover through this increased awareness that we tend to reach for food when we’re anxious, bored, or stressed, rather than when we’re truly hungry. By becoming aware of these patterns, we can work to break them and replace them with healthier behaviors. On the other hand, we may learn to appreciate the sensation of satiety and to stop eating when we’re no longer hungry, rather than when we’re full. This heightened awareness allows us to redefine our relationship with food, shifting it from a source of comfort or reward to a source of nourishment and sustenance.

Thus, as we navigate the path of fasting, it’s crucial to remain mindful and sensitive to our internal experiences. This process isn’t just about reducing our food intake; it’s about reshaping our relationship with food and understanding its profound impact on our mental and physical wellbeing. When approached with awareness and sensitivity, fasting becomes a powerful tool for personal growth and self-improvement.